Teaching children how to act has been on the minds of parents and authorities since the written word. From Puritanical subjugation to laissez-faire families, physical punishment to positive discipline, the best method of parenting has long been a debate.

Take it from the Old Testament, strict corporal punishment has been a popular form of discipline for a long time. Proverbs 29:15 offers parenting advice in the form of, “the rod and reproof” which it says “give wisdom” while a “child left to himself bringeth his mother to shame.” Yes, strict discipline methods were generally accepted for millennia, but there is history of dissent that is just as deep.

Even in the Medieval era, an age that put heretics on the rack and subjected adulterous women to breast rippers (yes, that’s the technical title), physical harm to children was far more controversial than violence towards adults. In a report from the University of Exeter, Nicholas Orme details how, during biblical times, “corporal punishment was in use throughout society and probably also in homes, although social commentators criticized parents for indulgence towards children rather than for harsh discipline.”

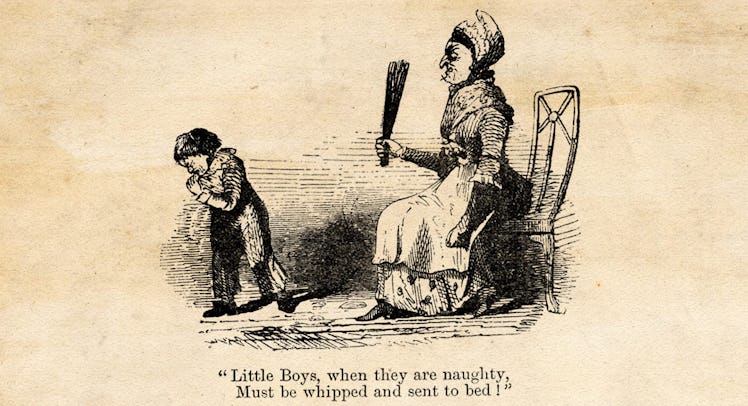

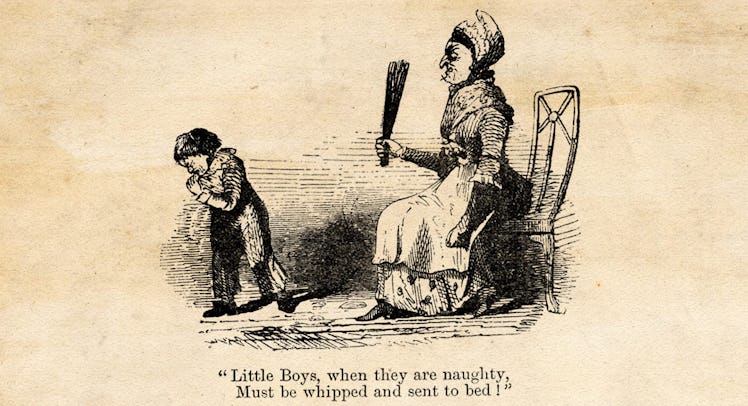

As Puritans rose against the English church, the subjugation of children was formalized, dissuading them against challenging or rebelling against authority in the slightest. Puritan children were taught that by disobeying their parents they were forcing God to condemn them to eternal death, and that strong discipline — i.e. physical punishment — could bring salvation to children. “If disobedient, children were whipped in public and forced to make public confessions at meetings. Matters such as rights of children were never considered,” states research from the Journal of Child and Family Studies.

Not everyone fully bought into the harsh corporal punishment of this time. John Locke, the English philosopher and physician who is commonly referred to as the “Father of Liberalism,” wrote parenting guidelines that at the time weren’t popular, but foreshadowed many of the positive discipline methods we see today.

In 1690, Locke published the Essay Concerning Human Understanding, and presented the idea that children resemble a blank tablet (tabula rasa) at birth, and they are not predisposed to sin. Locke encouraged 17th-century parents to have children learn about consequences naturally, so that self-control and a desire to be accountable for their own actions is a by-product of guidance, not harsh discipline.

“…according to the ordinary disciplining of children, [it] would not have mended that temper, nor have brought him to be in love with his book; to take a pleasure in learning, and to desire, as he does, to be taught more, than those about him think fit always to teach him. … We have reason to conclude, that great care is to be had of the forming children’s minds, and giving them that seasoning early, which shall influence their lives always after.”

The education system as a whole buried that message for centuries. By the early 1900s, some childrearing experts proposed new methods of “pressuring children into good behavior.” One method was called the “scorecard,” posted in the child’s home and gold stars or black marks were placed where it said “Rising on time,” “Cleaning up room,” “Writing to Grandma,” and other tasks and duties (sound familiar?). Punishments or rewards were then allotted accordingly.

The science of child rearing was becoming popular at this time and new experts and published theories created a more dynamic, and confusing, environment for parents caught between listening to a pastor or following new child-rearing philosophies — many of them spouting conflicting messages about how much permissiveness should be allowed versus how much discipline should be used. Some methods offered strict regiments to form eating habits, social tendencies, and sleeping habits; others pointed to “gentler” means of discipline, granting children more freedom.

In 1946 Dr. Spock released the now famous parenting tome, Baby and Child Care, which opens with the line, “You know more than you think you do,” and reassured parents all over the country that disciplining a child wasn’t a matter of following the orders of the status quo. He encouraged parents to be reasonable, consistent, open, and friendly with their kids — not regimented or authoritative. “Children are driven from within themselves to grow, explore, experience, learn, and build relationships with other people,” the latest edition of Baby and Child Care reads. “So while you are trusting yourself, remember also to trust your child.”

But when the first generation of Spock-raised babies turned into the rebellious teens of the 1960s and 1970s got to the scene, Dr. Spock’s ideas took a hit from the stricter, more regimented experts. Conservative psychologists such as James Dobson encouraged authoritarian parenting styles, and a clear divide was drawn between parents who spank children and non-spanking parents.

To this day, the U.S. displays a divided attitude towards spanking and corporal punishment. While domestic corporal punishment is illegal in more than 50 countries around the world, that’s not the case in America, where 17 states still allow corporal punishment in their public schools.

Discipline isn’t, by definition, a bad thing. Studies have shown that the most effective way to foster healthy relationships with children and give them the ability to learn and utilize self-control is through positive discipline. According to the book No More Perfect Kids: Love Your Kids for Who They Are, positive discipline is based on minimizing the child’s frustrations and therefore reducing misbehavior rather than giving punishments. The “Golden Rule” is the guiding light with positive discipline — encouraging children to feel empowered, in control, and good about themselves while also building a positive parent-child relationship. “You can’t change whom your child is,” says Sharon Silver, founder of Proactive Parenting. “But you can make adjustments so that they have the opportunity to learn about who they are and be the best version of themselves within the boundaries you set.”